Can a tool of segregation be used to fight displacement?

The delicate balance of residential preference policies

By Eve Bachrach and Michael Lens

Concerns over gentrification and displacement in California’s cities are reaching fever pitch. Rises in housing costs are outstripping income gains, and many residents are being pushed out of central city neighborhoods that have been affordable to low-income workers for decades. In San Francisco, where the high-paying tech industry has attracted so many new residents to the city—and where housing construction has lagged population growth for many years—the problem is particularly acute.

In 2015 the city adopted a policy that sets aside a portion of units in city-funded affordable housing developments for current residents of that neighborhood. The Neighborhood Resident Housing Preference (NRHP) is the City’s bid to slow the displacement of low-income residents from particular neighborhoods, and the city as a whole.

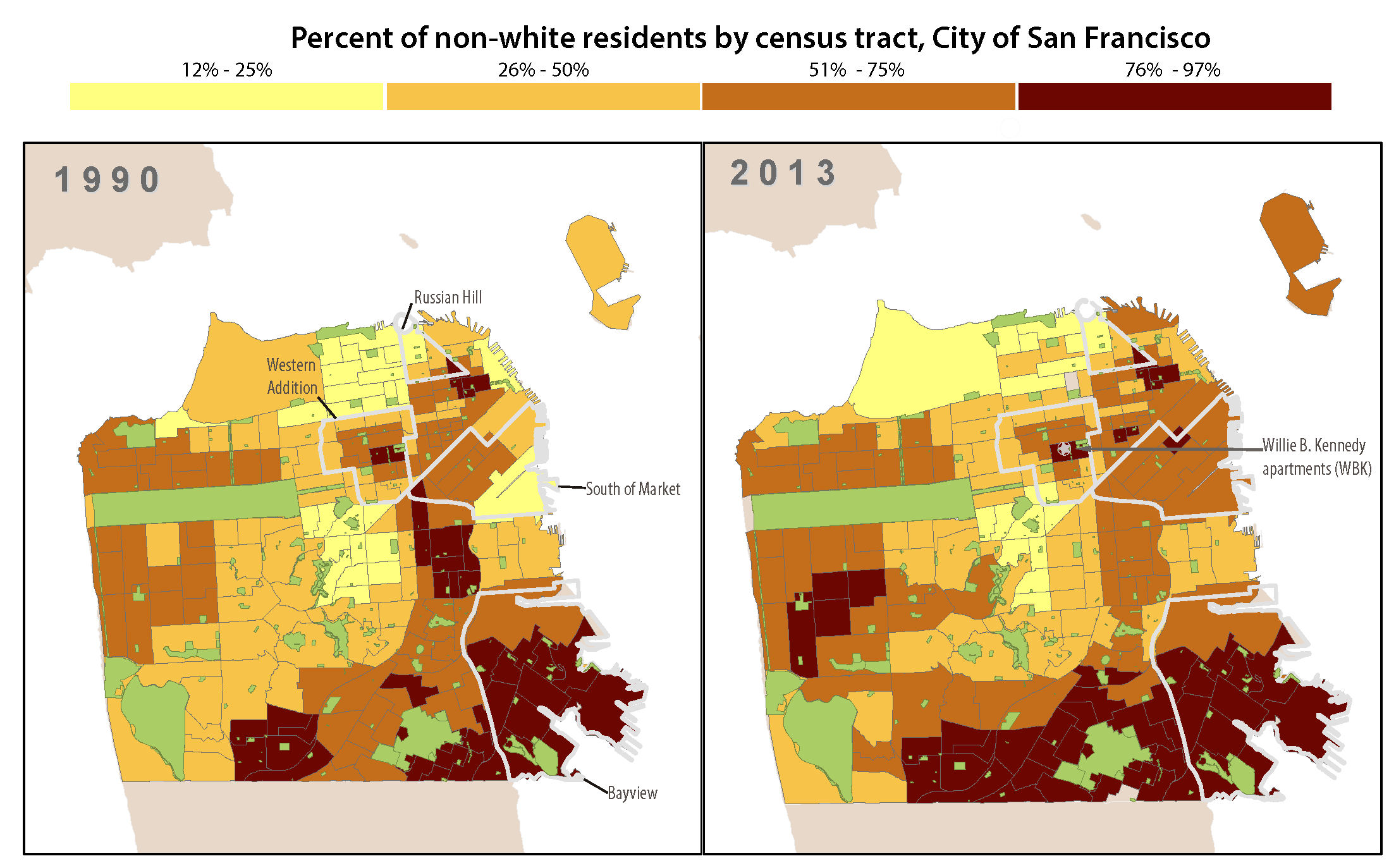

How can cities actively curb displacement? Researchers have found that neighborhoods that have been more successful in resisting gentrification and displacement have done so through a range of proactive measures, from strong tenants’ rights provisions to condominium conversion ordinances. Neighborhood preference policies like San Francisco’s can be found across the country, and they are controversial. Their history is steeped in racism when specifying who was allowed to live in particular neighborhoods prohibited people of color from all-white neighborhoods. Because of this history, neighborhood preference policies are illegal under the Fair Housing Act, and the federal government has successfully sued local housing authorities for using them. Yet San Francisco is attempting to use a neighborhood preference policies to maintain diversity in what have traditionally been mixed neighborhoods. Can these policies be used effectively and fairly to slow gentrification and protect residents at risk of displacement?

Neighborhood Resident Housing Preference and the Willie B. Kennedy Apartments

The details of neighborhood preference policies vary by location. San Francisco’s version, the NRHP, sets aside 40% of units in new affordable housing developments funded or administered by the city for qualified residents who either live in the Supervisory district in which the development was built, or within a half-mile of the development. It applies only to the initial lease-up of a building, and only to buildings that include five or more units.

The policy made headlines in August 2016 when the city tried to apply the NHRP to a new affordable housing project in the Western Addition, a historically Black neighborhood where displacement is a rising challenge. The 98-unit Willie B. Kennedy Apartments (WBK) was built for formerly homeless seniors and people over 62 who earn less than half the area median income. Because the development was funded in part by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), HUD reviewed the city’s plan for filling the new affordable housing units. HUD rejected the plan, saying it would “not approve the Supervisorial District preference because it could limit equal access to housing and perpetuate segregation,” and that the policy might be a violation of the Fair Housing Act.

In San Francisco’s defense of the policy to HUD, city attorney Dennis Herrera argued that the NRHP was designed not to reinforce segregation but to stabilize a diverse neighborhood that was becoming less so. He noted that the NRHP was in line with the Fair Housing Act because, in seeking to limit the displacement of minorities in the Western Addition, it would protect members of a protected class – San Francisco’s Black population – which is at particular risk of displacement. The Black population in San Francisco has decreased by nearly 20% since 2000, in part because they have been largely shut out of the high-paying tech jobs that make the city’s rents affordable. Herrera argued that the NRHP would help San Francisco achieve HUD’s objective of creating (or maintaining, in this case) integrated communities.

In September 2016, HUD and San Francisco reached an agreement that allowed the city to give preference to some residents based on where they lived when filling WBK’s units. Instead of setting aside 40% of the apartments for residents of the immediate neighborhood, those units would go to residents of neighborhoods facing “extreme displacement pressure” as defined by a recent UCB/UCLA study of urban displacement. This Non-Displacement Housing Preference means that qualified residents of Bayview, Russian Hill, South of Market, the Mission, and WBK’s Western Addition neighborhood would all be eligible for the set-aside units.[10]

“San Francisco’s version, the NRHP, sets aside 40% of units in new affordable housing developments funded or administered by the city for qualified residents who either live in the Supervisory district in which the development was built, or within a half-mile of the development.”

The Issue of Displacement and Segregation

The fight over neighborhood preference for WBK was resolved, but questions over the use of policies like it to combat both displacement–and in particular, displacement that leads to segregation–around the country is still an open one. In 2015, the New York-based Anti-Discrimination Center sued the city of New York over its decades-old version of the policy, saying it was in violation of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Defenders of the policy say it is necessary to “maintain stable, diverse neighborhoods in the face of continuing gentrification and housing price increases,” and ensures that longtime residents of a neighborhood are not forced out once that neighborhood becomes more desirable. Critics note, however, that the “stable, diverse neighborhoods” the preference preserves are still not particularly integrated. Neighborhood preference freezes them in a state of quasi-integration.

But even if neighborhood choice could successfully halt the resegregation that can accompany displacement, it would still fall short of HUD’s goal of creating integrated communities. The department recommitted itself to that aim in 2015 with its Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule, which requires communities to take “meaningful actions” to replace “segregated living patterns with truly integrated and balanced living patterns, transforming racially or ethnically concentrated areas of poverty into areas of opportunity.” How this relates to neighborhood preference is a bit of a gray area. On the one hand, neighborhood preference is a “meaningful action” that can slow segregated patterns from forming. On the other hand, as critics have noted, it cannot turn back segregation where it already exists.

If the AFFH rule and neighborhood preference are in tension it is because they are responses to two very different causes of segregation. Neighborhood preference is being used to slow displacement, whereas AFFH was crafted in response to what has historically been the barrier to housing integration: predominately white neighborhoods barring Black people from moving in.

Chicago and Los Angeles: Case Studies in Neighborhood Preference and Gentrification

The legacy of segregation is still with us. In Chicago, where former HUD Secretary Julian Castro announced the AFFH rule, predominately Black neighborhoods have remained unchanged for decades as their residents have been unable to move to affordable housing elsewhere. The new rule requires regions like Chicago and its suburbs to scrutinize these persistent patterns of housing segregation, take action to remedy them, and regularly report back on their progress.

In the context of Chicago, the idea that neighborhood preference could “perpetuate segregation,” as HUD warned San Francisco its policy might, is perfectly understandable. But the drivers of San Francisco’s current housing segregation are different from Chicago’s. Rather than being trapped in certain neighborhoods, many of San Francisco’s Black residents are being priced out. Los Angeles, where rising rents are forcing minority residents out of what have long been affordable neighborhoods – and are prohibitively expensive for those seeking to move into those neighborhoods – shares San Francisco’s conundrum.

In Los Angeles, activists and researchers are similarly sounding the alarm about gentrification. Neighborhoods like Boyle Heights, Highland Park, and communities across South LA have for decades been home to low-income people of color, and residents of each are grappling with gentrification and displacement. They are concerned about the process of neighborhood change that includes not just the arrival of art galleries, cafes, and new luxury apartment buildings, but also rent hikes and housing demolition that pushes out long-term residents. East of downtown LA, in Boyle Heights, the demolition of a handful of single-family houses to make way for 50 apartments for low-income renters drew anti-displacement protests because the housing developers could not guarantee a place for each displaced family in the new building. Would the response to this project have been different if Los Angeles had a neighborhood preference policy in place? And would such a policy be effective? The intensity of anti-gentrification protests in Boyle Heights has made headlines around the world, and fights like this, make clear that what is at stake is more than just typical dynamics of neighborhood and urban change. Communities are responding to generations of disenfranchisement, and feel the need to mobilize aggressively to protect their housing, communities, and ways of life.

But the drivers of San Francisco’s current housing segregation are different from Chicago’s. Rather than being trapped in certain neighborhoods, many of San Francisco’s Black residents are being priced out.

Housing Conflict in Boyle Heights

Some in Boyle Heights and other low-income communities in Los Angeles are calling for a right of return for those displaced by development. This is a version of a neighborhood preference policy. Rather than give preference to existing residents of a neighborhood, a right of return would guarantee housing in a new development to any household displaced by its construction. A right of return has been called for by tenants fighting specific developments, and as a citywide policy by housing advocates. In its statement in support of Measure S in February 2017, the Los Angeles Tenants Union criticized the absence of a guaranteed right of return to protect the city’s renters. (Measure S, a controversial ballot initiative that would have stopped nearly all development in Los Angeles for two years, failed in March 2017, and also did not include a right of return for residents displaced by development.)

Boyle Heights is a particularly interesting place to consider displacement and the conflict between the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule and neighborhood preference. Like the neighborhoods the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule is intended to target, Boyle Heights is notable for its lack of integration—94% of residents are Latino. Community groups such as Defend Boyle Heights organize with the explicit goal of fighting gentrification and the flow of capital from outside the neighborhood. This stance puts them in direct opposition to the AFFH objective of “transforming racially or ethnically concentrated areas of poverty into areas of opportunity.” By turning Boyle Heights into an “area of opportunity” the fear is that the existing community will be forced out as rents rise. This greatly complicates policies that seek to enhance neighborhood opportunity for low-income residents.

Where President Trump and new HUD Secretary Ben Carson stand on these issues is unclear, but there is longstanding Republican opposition to desegregation efforts like Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing. In January 2017, bills introduced in the Senate (S. 103) and House (H.R. 482) would nullify AFFH and defund the mapping tool that allows jurisdictions to identify segregated living patterns in their communities. Whether or not the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule is appropriate for every community, this does not bode well for the government’s commitment to fighting housing segregation.

Eve Bachrach is a Master of Urban Planning candidate at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. Eve has also served as associate editor on Curbed LA, as well as managing editor at Boom: A Journal of California. You can contact her on her twitter: @evaliceb . Michael Lens is Associate Faculty Director for the Lewis Center and Associate Professor of Urban Planning and Public Policy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. Paavo Monkkonen and Madeline Brozen contributed to this brief.

References

“AFFH Rule Guidebook.” (December 2015): 1-225. Web. 15 June 2017. <https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/AFFH-Rule-Guidebook.pdf>.

Badger, Emily. “Obama Administration to Unveil Major New Rules Targeting Segregation across U.S.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 08 July 2015. Web. 15 June 2017. <https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/07/08/obama-administration-to-unveil-major-new-rules-targeting-segregation-across-u-s/>.

“Board of Supervisors.” San Francisco Housing Development | Board of Supervisors. City and County Of San Francisco, 11 June 2003. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://sfbos.org/san-francisco-housing-development>.

“Boyle Heights.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, n.d. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://maps.latimes.com/neighborhoods/neighborhood/boyle-heights/>.

Cestero, Rafael. “An Inclusionary Tool Created by Low-Income Communities for Low-Income Communities.” Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. NYU Furman, Nov. 2015. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://furmancenter.org/research/iri/essay/an-inclusionary-tool-created-by-low-income-communities-for-low-income-commu>.

Cestero, Rafael. “An Inclusionary Tool Created by Low-Income Communities for Low-Income Communities.” Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. NYU Furman, Nov. 2015. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://furmancenter.org/research/iri/essay/an-inclusionary-tool-created-by-low-income-communities-for-low-income-commu>.

Foulsham, George. “Gentrification and Displacement in Southern California.” UCLA Luskin. N.p., 26 Jan. 2017. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://luskin.ucla.edu/2016/08/29/gentrification-displacement-southern-california/>.

Fuller, Thomas. “The Loneliness of Being Black in San Francisco.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 20 July 2016. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/21/us/black-exodus-from-san-francisco.html?_r=0>.

Gonzales, Richard. “Feds To Allow Preferences For Low-Income Applicants In S.F. Housing Complex.” NPR. NPR, 23 Sept. 2016. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://www.npr.org/2016/09/23/495237494/feds-to-allow-preferences-for-low-income-applicants-in-s-f-housing-complex>.

Herrera, Dennis J. “Neighborhood Preference Implementation in San Francisco.” Herrera urges HUD to reconsider . Office Of The City Attorney, 25 Aug. 2016. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://www.sfcityattorney.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Herrera-to-HUD-2016-0 8-25.pdf>. Letter to HUD Secretary and General Counsel

“Urban Displacement Project” UCLA and UC Berkeley. Accessed 15 June 2017. <http://www.urbandisplacement.org/>.

“Los Angeles Tenants Union Statement In Support Of Measures S.” N.p., 13 Feb. 2017.Web. 15 June 2017. <https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/crenshawsubway/pages/98/attachments/original/1487377016/LATU_Statement_on_Measure_S.pdf?1487377016>.

Misra, Tanvi. “The Long War on the Fair Housing Act.” CityLab. N.p., 07 Feb. 2017. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://www.citylab.com/housing/2017/02/fair-housing-faces-an-uncertain-fate/515133/>.

“QuickFacts.” U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts Selected: San Francisco County, California. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/AGE115210/06075>.

Ramey, C., & Kusisto, L. (2015, Jul 07). Group challenges new york city on housing allocations; lawsuit alleges that the city-wide policy of ‘community preference’ violates the fair housing act of 1968. Wall Street Journal (Online) Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1694581834?accountid=14512

Radio, Southern California Public. “Tenant Activists Divided over LA Housing Initiative.” Southern California Public Radio. N.p., 10 Feb. 2017. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://www.scpr.org/news/2016/10/24/65720/tenant-rights-group-splits-from-the-rest/>.

“REBELLION IN BOYLE HEIGHTS.” Red Guards Los Angeles. N.p., 03 Dec. 2016. Web. 15 June 2017. <https://redguardsla.org/2016/09/20/rebellion-in-boyle-heights/>.

“San Francisco, California Population:Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts.” San Francisco, CA Population – Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts – CensusViewer. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://censusviewer.com/city/CA/San%20Francisco>.

Schwemm, Robert G. “The Community Preference Policy: An Unnecessary Barrier to Minorities’ Housing Rights.” Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. NYU Furman Center, Nov. 2015. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://furmancenter.org/research/iri/essay/the-community-preference-policy-an-unnecessary-barrier-to-minorities-housin>.

“Tenants Protest against ‘displacement’ by ELACC.” Boyle Heights Beat. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://www.boyleheightsbeat.com/tenants-protest-against-displacement-by-elacc-11751>.

“The Community Preference Policy: An Unnecessary Barrier to Minorities’ Housing Rights.” NYU Furman Center. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 June 2017. <http://furmancenter.org/research/iri/essay/the-community-preference-policy-an-unnecessary-barrier-to-minorities-housin>.

“Urban Displacement Project: Executive Summary” UC Berkeley, December 2015. <http://www.urbandisplacement.org/sites/default/files/images/urban_displacement_project_-_executive_summary.pdf>.

Velasquez, Gustavo. “U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.” 03 Aug.2016. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 June 2017.<http://www.trauss.com/pdfs/WBK_neighborhood_preference.pdf>.

Velasquez, Gustavo. “U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.” San Francisco Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, 21 Sept. 2016.Web. 15 June 2017. <http://sfmohcd.org/sites/default/files/WBK%20Ltr%209%2021%202016.pdf>.