Is Los Angeles Destroying Its Affordable Housing Stock to Build Luxury Apartments?

By Eve Bachrach, Paavo Monkkonen, and Michael Lens

Los Angeles needs to build more housing. A key driver of the city’s affordability crisis is that the pace of building has not kept up with the increase of new residents over the past three decades. This, however, is where the consensus ends. Arguments persist over new housing — where it should be built, how dense, and for whom.

New, densely-built infill housing is more environmentally friendly than homes built on the urban periphery, as it allows residents to live closer to transit and employment. Yet new infill housing is often more expensive to rent or buy than older multifamily units nearby, and thus provides little immediate relief to the low-income households that have been squeezed the tightest by rising rents. So many fear that, because LA is short on vacant parcels zoned for multifamily homes, old (affordable) units will inevitably be demolished to make way for new (expensive) housing.

But is this really happening? Is Los Angeles cannibalizing its affordable rental housing to make way for market-rate and luxury apartments?

If so, it would be a serious rebuke to those that contend that the solution to the city’s housing crisis is to remove as many impediments to development as possible and let the market solve the problem. Others believe that the city’s current housing shortage is so broad that it affects people of just about every income level. Their concerns are that market-driven solutions to the housing crisis are focused on the needs (real as they may be) of the relatively well-off — at the direct expense of poorer households.

To learn more, we looked at records for new multifamily development that opened in the city of Los Angeles between 2014 and 2016 to determine what was demolished to build that new housing. Where possible, we also logged the rental costs of these new units. During the three-year period, 13,749 units opened in 971 multifamily developments. Given the logistical difficulties in identifying the form and price of new and demolished stock, we randomly selected 104 developments to conduct our in-depth analysis.

Key findings

- 26 of the 104 new housing developments were built on vacant or nonresidential parcels.

- 59 of the 78 existing buildings demolished to make way for new development were single-family homes.

- Only one new development in the sample contained fewer residential units than the buildings it replaced.

- Most new multifamily housing units were duplexes. 38 percent of new multifamily buildings in our sample had 10 or more units.

- South Los Angeles has seen the majority of new duplex development (79 percent). Many of these buildings replaced single-family houses smaller than 1,000 square feet with larger apartments of four or more bedrooms apiece.

- Of the handful of luxury apartments that replaced small, older multifamily buildings, several were near the UCLA and USC campuses.

Housing lost and gained

In our analysis of 104 new multifamily developments, we found that more than 13 times as many units were constructed across the city than were demolished (see Table 1). We also found that 22 percent of the new units were affordable — income-restricted and/or permanent supportive housing for formerly homeless people. There were 460 such units, which is more than six times greater than the number of multifamily units lost to demolitions. This is important because older multifamily units are the sort of naturally-occurring affordable housing that most concerns activists.

Table 1: Units lost and gained in a random sample of developments from 2014-2016[1]

| Housing Units Demolished | Housing Units Constructed |

| 152 | 2061 |

| Multifamily Units Demolished | Affordable Units Constructed |

| 74 | 460 |

This is good news — according to our findings, new housing development is mostly replacing single-family housing, creating many more units than it is demolishing and even producing many more strictly affordable units than what is demolished. Yet there are other factors to consider. The distribution of new units across the city matters, as does the match between unit and neighborhood types.

Moreover, not all affordable units are alike. Some new developments are permanent supportive housing for homeless people, some are for seniors, and other have rents pegged to different percentages of the county’s median income. While we are building more affordable units than we are demolishing, that does not mean that the 74 households in our sample who moved out of those demolished multifamily units are able to afford what replaces it. New affordable housing construction can benefit the city as a whole at the expense of individual households.

New multifamily construction is more common in (but not exclusive to) the denser or more central parts of the city, such as South LA and Hollywood. In the San Fernando Valley, which is about half as dense as South LA,[2], [3] our sample had 18 new multifamily developments. While this is a relatively small number considering the Valley is roughly half of Los Angeles’s square footage, these developments tended to be larger than those built in South LA. Very little of this activity was on the Westside of Los Angeles.

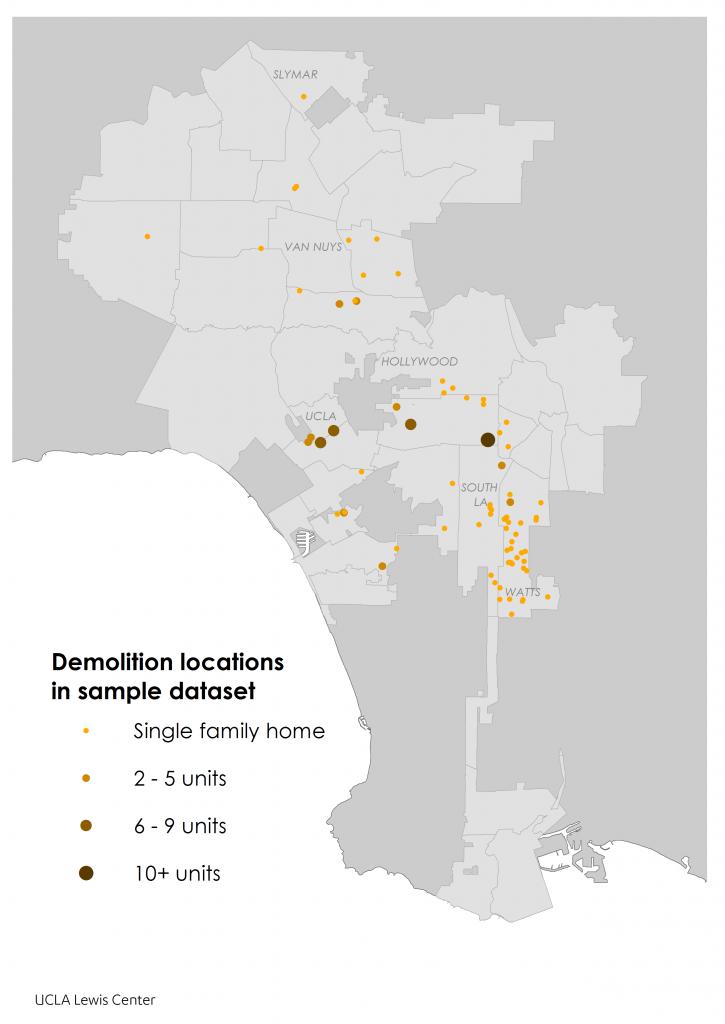

Demolitions

Where is housing being torn down? The maps here show where housing units were demolished across the city of Los Angeles in order to build new multifamily buildings. Figure 1 displays the 68 developments in our sample that required the demolition of one or more single-family houses, as well as the 11 developments in the sample that required multifamily buildings to be demolished. While single-family houses were demolished in many parts of the city, there was a large cluster of demolitions in South Los Angeles neighborhoods such as Watts and Florence. Notably, very few single-family homes were demolished on the Westside. Seven of the demolished multifamily buildings were in central neighborhoods north of the 10 freeway and south of the Hollywood Hills. These centrally-located buildings contained more than two-thirds of the units lost in multiple-unit demolitions in the sample. Note that the map merely shows housing unit demolitions, not net housing units lost, and does not include the 26 new housing developments built on previously vacant or nonresidential parcels.

Figure 1: Single houses and multifamily units demolished to build multifamily housing in the sample

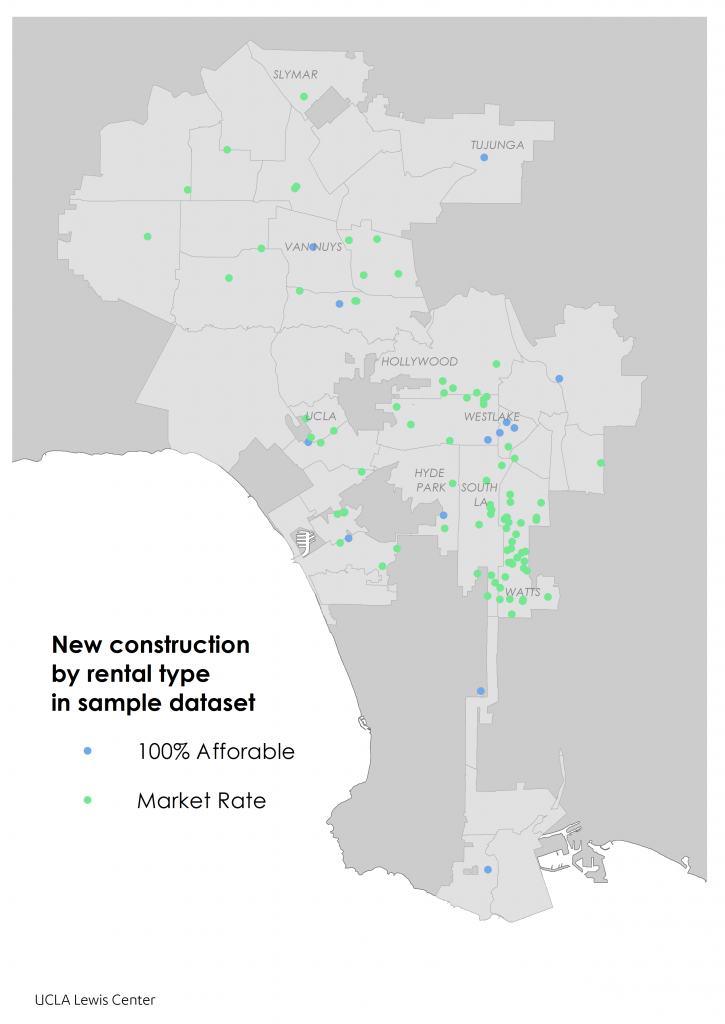

New construction and affordable developments

Figure 2: New multifamily developments

Of the 104 developments in our sample, we designated 12 as 100 percent affordable — buildings that peg rent to some fraction of a resident household’s income that is below some fraction of LA County’s median income. Most of these developments are restricted to a certain segment of the population: Low-income seniors who are HIV positive, homeless veterans, artists, or those with special needs. Some of these affordable developments were built in neighborhoods where, according to a Los Angeles Times mapping project, the median household income is about average for the city, such as Tujunga. One is in a high-income neighborhood, Playa Vista, which has also been the site of hundreds of luxury housing units. But the majority are in lower-income neighborhoods such as Westlake, Glassell Park, and Hyde Park. A handful of market-rate developments do also include some units for low-income and very-low-income renters.

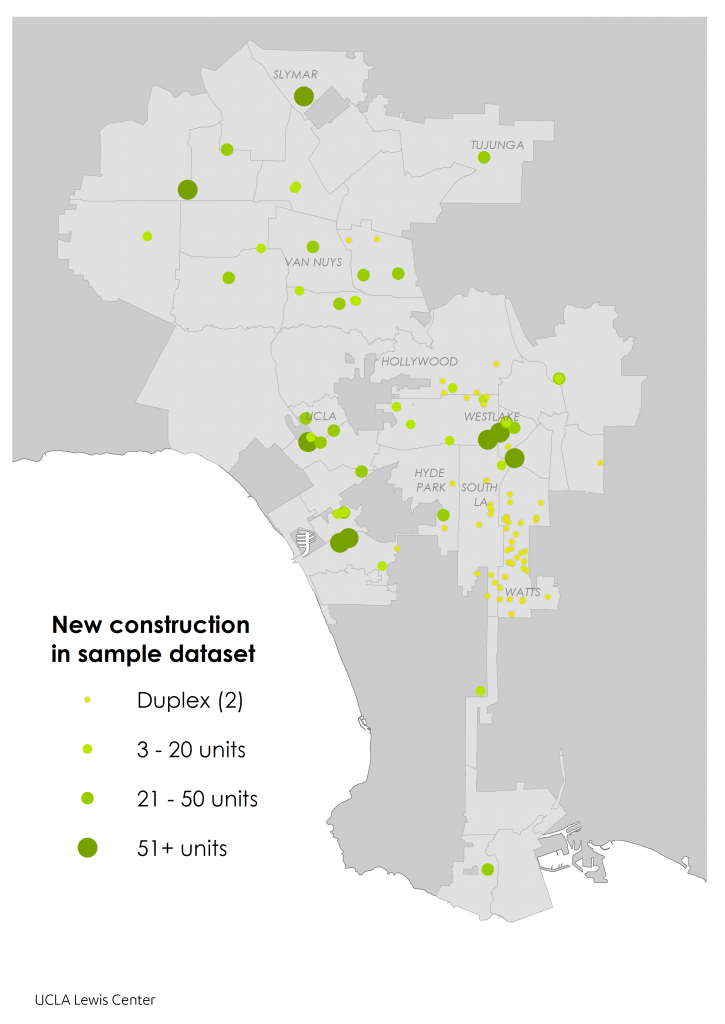

New construction by number of units

Figure 3: New multifamily construction by size

Fifty-nine of the 104 new developments in the sample are duplexes, mostly concentrated in South LA. Larger multifamily development has been somewhat more evenly spread across the city. Downtown, Westwood, and Westlake each have multiple developments of 24 or more units, but further-flung neighborhoods from San Pedro to Sylmar have also seen denser development. However, our sample did not include any multifamily construction in wealthy Westside neighborhoods outside of Westwood, such as Brentwood, Pacific Palisades, or Cheviot Hills.

Rents

According to US Census data, the median household income in Los Angeles between 2011 and 2015 was $50,205.[4] For a monthly rent to be considered affordable, it must be at or below 30 percent of a household’s monthly income — so $1,255 for LA. We found rental listings for 49 of the market-rate developments in our sample. None would be considered affordable to a median household. A one-bedroom apartment in Sylmar advertised for $1,300 came the closest to affordability for a household earning a median income in the city.

But this is not to say that all new apartments are amenity-laden luxury units affordable only to the very wealthiest Angelenos, either. Some are, such as the $3,605/month one-bedroom apartment in Playa Vista that comes with a private wine cellar. Our list also includes a $2,025/month two-bedroom apartment in Granada Hills, built on the site of a former retail structure; a $2,350/month two-bedroom apartment in Northridge, one of 338 units also built on the site of a former retail structure; and an 8-unit building in Mid-Wilshire built on vacant land, with a two-bedroom apartment renting for $2,500/month. These rents are only affordable for 20 to 30 percent of Los Angeles households. However, the median rent for all apartments in Los Angeles of $2,100 is also unaffordable to a household earning the median income.[5]

We also found several new four- and five-bedroom duplex units in South LA listed for roughly $2,500/month. These large apartments tended to replace much smaller single-family homes. Many duplexes — indeed most of the ones we researched — were built by a single company, Ocean Development, Inc. (ODI), and are eligible for Section 8 rental subsidies.[6]

Conclusion

Our sample of new multifamily construction between 2014 and 2016 makes us cautiously optimistic. Los Angeles has not been systematically trading affordable housing units for luxury units for its wealthiest residents. While some low-cost housing has been lost, the vast majority of new multifamily units — both market-rate and income-restricted affordable apartments — have replaced single-family houses or been built on land not previously used for residential development. Not only are we not losing large numbers of naturally-occurring affordable housing, but our randomly-selected sample found six new affordable units built for every unit demolished.

But there is also cause for concern. First, because we wanted to see what new multifamily developments replaced, we bypassed demolitions that did not result in new rental apartments. If an apartment building was demolished to make way for a single-family home, which does occasionally happen, or for an as-yet unbuilt apartment, we did not include it in this analysis. Second, there is a clear geographic pattern to new multifamily housing construction, and very little is being built on the Westside. The densifying neighborhoods are concentrated in central and south Los Angeles, communities that are on average poorer than the rest of the city. LA’s wealthier neighborhoods are not making room for the new housing everyone agrees must be built.

Though we did not find market-rate apartments affordable to median-income households in Los Angeles, this criticism applies to all apartments in Los Angeles. New rental units are unaffordable to the median household in the city because all rental units are unaffordable to the median household. Moreover, expanding housing supply, even at rents above the average, is important. Increasing the availability of rentals for higher-income renters at a minimum will make them less likely to outbid households with lower incomes for the older rental units. If the city allowed even more multifamily units to be built, especially in wealthier neighborhoods, it would reduce the tendency of landlords to rehab their older buildings and push out their existing tenants.

Eve Bachrach is a Master of Urban Planning candidate at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs and previously served as associate editor for Curbed LA and managing editor for Boom California. Paavo Monkkonen is the Lewis Center senior fellow for housing policy and an associate professor of urban planning at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. Michael Lens is the associate faculty director for the Lewis Center and an associate professor of urban planning and public policy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs.

Methods appendix

This preliminary analysis of demolitions and new housing is based on a sample of new multifamily housing issued a Certificate of Occupancy by the City of Los Angeles between 2014 and 2016. A fuller analysis of all new multifamily units is underway.

Researchers downloaded a list of all residential properties issued a certificate of occupancy in 2014, 2015, 2016, excluded all properties with fewer than two units, and divided the list into three by year, and sorted each list by number of units. Using a random number generator (RNG), we picked at least 10 properties from each list in each of two categories: Those with 10 or more units and those with 10 or fewer units. If the RNG selected a property of condominiums rather than rental units, we noted this and chose a new address. Once at least 20 properties for each year had been chosen, we then used the RNG to select additional properties from each of the full three lists until we had more than 100 addresses in my sample.

The previous use was determined by the most recent demolition permit associated with each address. If no recent demolition permit was on file, we attempted to find the previous use through property records.

Rents were determined by listings found on property, developer, and realtor listing sites, and free listing sites such as Craigslist, Padmapper, and Apartments.com. Where a property had more than one of a unit type listed, the rent was recorded as a range. If no listings less than one year old could be found, no rent was recorded. If more than one rent for the same unit was discovered, the most recent rent was recorded. It is important to note that these listing prices are a good indicator of apartment rent, but they are not necessarily identical to the actual rent.

Research was conducted in March and April of 2017.

References

[1] This number includes only units built in 100 percent affordable units and therefore undercounts the total number of new affordable units constructed.

[2] http://maps.latimes.com/neighborhoods/region/san-fernando-valley/

[3] http://maps.latimes.com/neighborhoods/region/south-la/

[4] https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/15_5YR/S1901/1600000US0644000

[5] The median rent in Los Angeles was calculated by averaging the median rent for the city in the three most recent Zumper Los Angeles Metro Reports