Overcoming Opposition to New Housing

By Paavo Monkkonen and Will Livesley-O’Neill

California’s housing crisis has sparked a necessary dialogue about displacement, gentrification, and neighborhood control over land use. In these discussions, more attention ought to be paid to the spatial inequality that governs housing development and how cities have arrived at their highly unequal distribution of density and development. Although many people agree that the state’s unprecedentedly high housing costs are the result of a severe housing shortage — one that hurts renters and benefits homeowners — they disagree about where this needed new housing will be built.

Not surprisingly, there is significant resistance to new construction from those that benefit most from its scarcity: Homeowners and landlords. Too few are advocating for upending the existing pattern of zoning and increasing construction in neighborhoods of opportunity, which currently exclude low- and middle-income households. How can we reform our planning systems to increase supply on the one hand, and to reduce the unequal spatial distribution of new development on the other?

To find pragmatic, implementable policy solutions, we must first take stock of what barriers prevent necessary new housing from being built in the neighborhoods with the highest demand. Researchers at UCLA examined the tactics available to opponents of new housing development and categorized the motivations behind anti-development sentiment. Mapping the structural motivations of neighbors and the diversity of tools that can block or scale back a project reveals the size and shape of the problem. Identifying the most salient motivations behind opposition to housing construction can help us overcome these barriers with far-reaching solutions.

Why must we address opposition to new and affordable housing and density in general?

Limiting the supply of housing in the face of stable or growing demand pushes rents up. Academic research consistently finds that constraints to urban infill and urban expansion, such as restrictive zoning, historic preservation ordinances, or multiple independent reviews, increases the price of housing.[1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7] Second, the way we decide where new housing is permitted exacerbates existing spatial inequalities. Excluding multi-family housing with low-density zoning prices low- and middle-income households out of neighborhoods with quality public services, particularly high-performing schools,[8] as well as amenities such as parks. Barring families from high-opportunity neighborhoods entrenches inequality and reduces social mobility in the long run.[9],[10],[11]

Low-density zoning also hurts the regional economy. Less housing makes it harder for workers to find a place to live. The city, unable to house workers, becomes less appealing to firms that rely on a local labor pool. Pushing people elsewhere incentivizes firms to locate elsewhere. A city that can’t house workers stunts its own potential for economic growth and dynamism.[12],[13] California’s high housing costs appear to be driving an exodus of tech start-ups from the Bay Area to places like Phoenix, Boise, and Salt Lake City.[14] The main group to benefit from higher housing prices is existing property owners — both landlords and homeowners. In a sense, preventing newcomers from moving to urban areas with strong economies allows existing landowners to capture and hoard the productivity gains that were produced collectively.[15]

Current residents are structurally incentivized to oppose newcomers

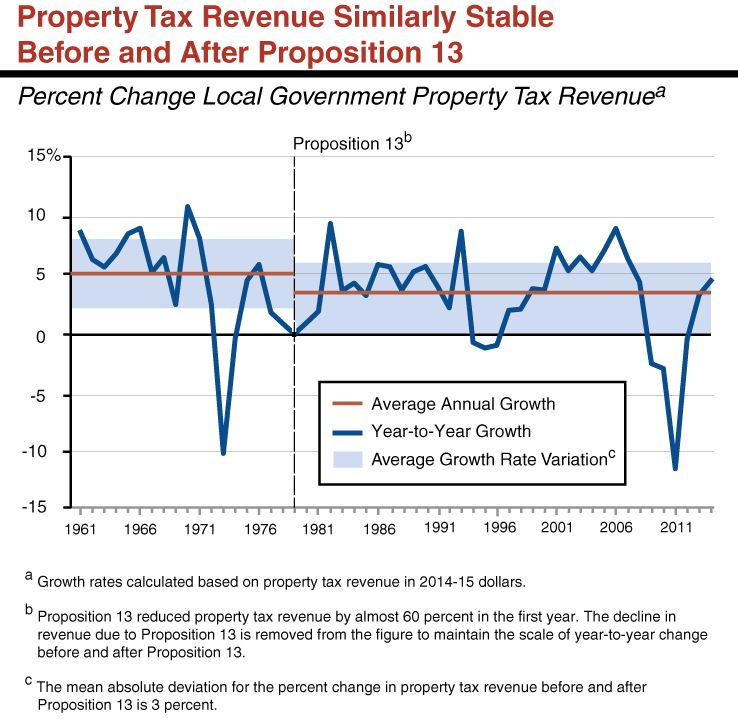

California’s property tax system, as regulated by Proposition 13, reassesses property values — and therefore property taxes — only when the property changes hands. This is a boon for longtime homeowners and landlords whose assessed values are far below the current market value. It also shapes the politics of planning for more housing. If existing homeowners had to pay their fair share in property taxes, rising home values would make them more amenable to solutions that dampen price increases.

Figure 1:

Another result of Proposition 13 is that municipal governments lose out on needed revenue and turn to impact fees and other sources to make up for the lost funds. The permit approval process for new housing is increasingly seen as a moment to recapture the land value, and cities ask developers of new housing to pay for community benefits, fund infrastructure, and add affordable housing units. Yet long-term owners and landlords face no such fiscal obligation to contribute to the market cost of the very amenities from which they benefit.

How can new housing help alleviate upward pressure on housing prices?

A recently built apartment is generally more expensive than a unit that has seen some wear and tear. But even though a brand new unit may be out of reach for most, at the metropolitan level, even expensive new units improve overall affordability. The way new building impacts localized housing markets is an understudied process, however, and will likely vary across metropolitan areas. Better empirical evidence is needed to understand how new construction relates to neighborhood change, and the clear distinction between regional and local housing market dynamics must be emphasized.

A process of filtering — high-income households moving into newer, more expensive units and freeing up existing older units for households with slightly lower incomes — is often used to explain the role of new housing in a housing market, though in many California cities it clearly does not occur.[16] And filtering will never occur if sufficient new housing is not built, such as in the case of California’s major metropolitan areas. On the contrary, when new housing is not available, high-income households tend to renovate and occupy older housing units that would otherwise become available to less well-off households.

A holistic housing policy requires prioritizing housing subsidies and other mechanisms to keep people in their homes, in addition to increasing housing supply to accommodate newcomers. A focus on supply as a solution to California’s housing crisis must acknowledge the displacement pressure new construction may create at the neighborhood level. Indeed, anti-displacement sentiment from long-term renters is one of the common drivers of housing opposition.[17] Although seemingly counterintuitive, blocking development does not prevent neighborhood change. Rents rise because of demand for housing and lack of supply, and this can displace households whether or not new luxury condominiums are built nearby.

Drivers of opposition to new housing

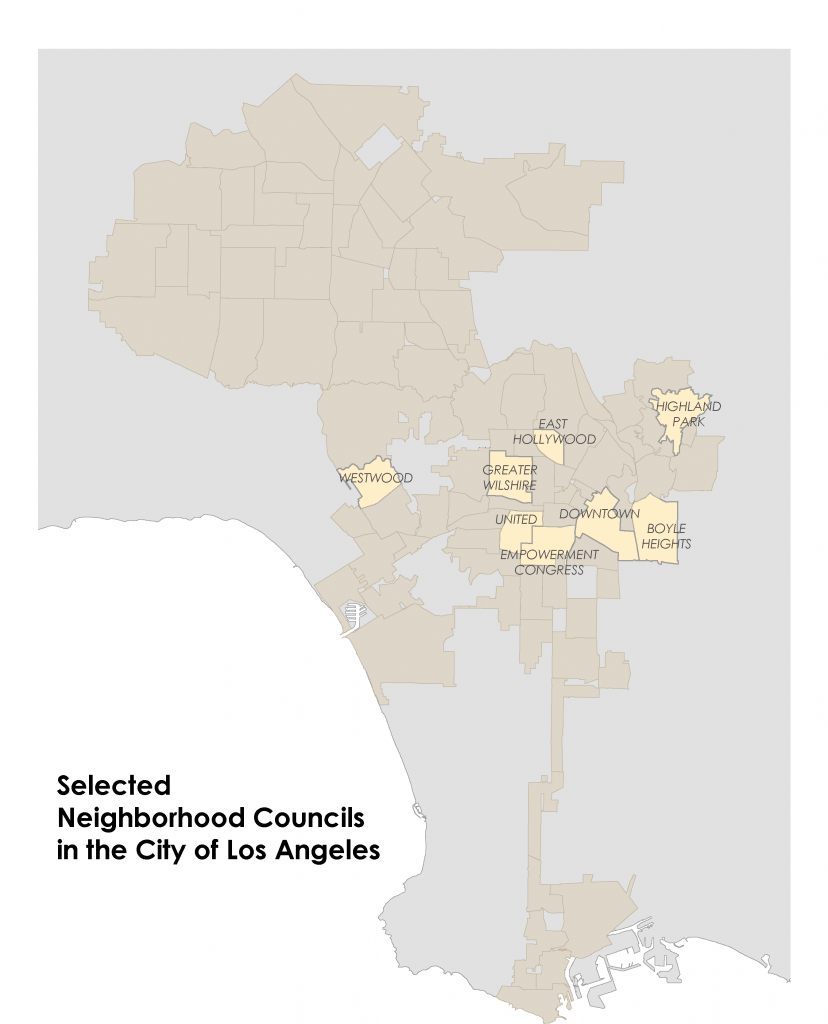

Based on our review of minutes from neighborhood council meetings in Los Angeles, and stakeholder interviews in both Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area, we distill the concerns that drive opposition to new housing into three categories: Concerns about the built environment, concerns about who lives near you, and concerns about the development process. See Table 1 for a summary of reasons for opposition to housing projects selected from public hearings in neighborhood councils throughout Los Angeles.

Figure 2: Map of selected neighborhood councils in Los Angeles

Table 1: Opposition to housing projects in Los Angeles neighborhood councils

| Neighborhood Council[18] | Reasons for Opposition to Housing Projects |

| Boyle Heights | Loss of tax revenue, higher costs associated with density, lack of engagement with the community, too much density already |

| Downtown Los Angeles | Blocked views, health and well-being, neighborhood character, historic preservation, lack of public/green space, higher rents |

| East Hollywood | Lack of engagement with the community |

| Empowerment Congress North | Lack of engagement with the community, influx of low income-residents |

| Greater Wilshire | Neighborhood character, aesthetics, scale, privacy, traffic congestion, pedestrian safety |

| Historic Highland Park | Neighborhood character, lack of engagement with the community, displacement/gentrification, environmental impact, too much density |

| United Neighborhoods | Neighborhood character |

| Westwood | Neighborhood character, historic preservation, legal precedent, environmental impact |

Source: Minutes of neighborhood council meetings, available online

Concerns about the built environment are dominated by anxiety about traffic congestion and access to parking, but also include general complaints about crowding and strain on local amenities.[19] Additional concerns about the quality of the nearby natural environment and maintaining property values could also fall under this category.[20]

Concerns about who lives near you are typically expressed in coded language. The vague catch-all term “neighborhood character” routinely surfaces as a complaint in wealthier neighborhoods, such as Greater Wilshire and Westwood. While the term can convey a range of meanings, who uses it and how suggests that the term can often be coded discrimination. Moreover, most homeowners who claim to want neighborhood stability do not acknowledge that price increases are a kind of neighborhood change.

Finally, objections to the housing development process have become common for opponents of new housing. They include condemnations of variances and discretionary review, allegations of political corruption in entitlement approvals, and complaints over a lack of community outreach. Developers are often portrayed as the unfair winners in times when new housing is expensive. Yet this ignores the fact that landlords and homeowners unfairly profit from housing scarcity to much greater degree.

The mechanics of opposition to new housing

By way of three overarching systems — planning, legal, and political — we estimate that local residents have approximately 20 formal avenues to oppose housing.[21] The more familiar veto points are appeals to specific projects or lawsuits under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). However, a number of broader, long-term tactics can be just as, if not more, effective, including stalling the community planning process, running ballot initiatives, or lobbying for state laws (see Table 2 for the complete list). The vocal advocacy of a handful of neighbors is often framed as local democracy, but many of these processes exclude the majority of a neighborhood’s residents and explicitly favor those with more money and time.

Table 2: Avenues to influence what does and does not get built

| Type of avenue | Methods | |

| Planning system |

|

|

| Legal system |

|

|

| Political system |

|

|

| Other avenues for expressing preferences |

|

Recommendations for addressing California’s housing opposition problem

- Enhance (and enforce) existing housing laws

California has one of the nation’s most comprehensive state housing laws, designed to encourage cities to consider their development needs and then set targets to meet those needs. The housing element law uses population projections to estimate how many new housing units will be needed in the state, and regional councils of government allocate these units to cities and counties, which are then required to update the housing element of their General Plans to accommodate future housing needs. While the framework is conceptually sound, it needs two major reforms: Enforcement and a methodology that makes sense.

First, the enforcement of our state law was virtually nonexistent until recently. Cities that fail to meet their housing targets have faced no consequences, and cities that achieve them have reaped no rewards.[32] A 2017 law, Senate Bill 35, has now created a long-needed enforcement mechanism to facilitate needed housing construction in cities that have not met their fair share goals. Further efforts along these lines should be considered, and new incentives to meet housing goals might be created.

Second, the way in which housing needs are currently calculated and allocated allow many cities to indirectly resist new housing. Future household formation is projected based on past trends, which biases estimates downward in places where increasingly expensive housing slows growth. This reinforces a process where higher-density places — often lower-income — get more housing needs allocated to them and lower-density places — often wealthier — get less. Furthermore, the way the regional councils allocate housing to cities does not have goals of improving affordability or environmental sustainability, and it should.

- Make the planning process more inclusive

The current planning process is not designed to solicit representative citizen feedback. Anecdotal evidence consistently suggests that certain groups are too loud and other groups are left without a voice. As currently structured, the feedback process requires individuals to have the resources to interpret proposals, stay regularly informed, travel to hearings during the workweek, and often wait hours to speak. A review of neighborhood council meeting minutes makes it obvious that discussion and decisions need to be made more understandable to the general public, especially people who speak English as a second language. Cities can tackle this problem on at least two fronts: Building in non-traditional platforms, such as social media and web forums, for broader inclusion, and disbanding the existing input channels that overrepresent older, whiter, and wealthier residents.

- Shift the scale of land use decisions from local to regional/state

Researchers find that when higher levels of government control land use decisions, rules are less exclusionary and reduce socioeconomic segregation.[33] There is a scalar mismatch in the governance of housing markets. Housing markets, like labor markets, operate at the regional level, yet land use decisions are made at the city level. As a result, each municipality is incentivized to limit its housing supply to exclude new residents of the region even as that municipality reaps the collective benefits created by the region’s economic dynamism. Moving the scale of political action on land use decisions to the regional or even state level would match the scale of the economic market, and would more accurately represent all those affected by land use decisions.

Conclusion

Opposition to new housing and increased housing density are major components of California’s current housing problem. In many of the state’s cities a vast majority of residential land is zoned only for single-family housing, which drastically limits potential supply. The fact that our planning system provides so many avenues to block changes to existing zoning creates an unequal spatial distribution of new housing development by concentrating most new housing production in places already zoned for multi-family or other uses, which tend to be lower-income neighborhoods. Thus, not only do we experience general affordability problems, we see gentrification and displacement in many neighborhoods, in particular. It is time to implement reforms to improve the way decisions are made over where and how much housing is permitted in California, and recognize that the status quo exacerbates inequality by benefiting homeowners at the expense of renters.

Paavo Monkkonen is the Lewis Center senior fellow for housing policy and an associate professor of urban planning at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. Will Livesley-O’Neill is the communications manager for the Lewis Center and the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies.

References

[1] Saiz, Albert (2010) The geographic determinants of housing supply. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(3), 1253–1296.

[2] Glaeser, Edward L., and Bruce A. Ward (2009) The causes and consequences of land use regulation: Evidence from greater Boston. Journal of Urban Economics 65(3): 265–278.

[3] Been, Vicki, Ingrid Gould Ellen, Michael Gedal, Edward Glaeser, and Brian J. McCabe (2014) “Preserving History or Hindering Growth? The Heterogeneous Effects of Historic Districts on Local Housing Markets in New York City.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 20446.

[4] Quigley, John M., and Steven Raphael (2005) Regulation and the high cost of housing in California. American Economic Review 95, 323–328.

[5] Kok, Nils, Paavo Monkkonen and John M. Quigley (2014) Land Use Regulations and the Value of Land and Housing: An Intra-Metropolitan Analysis. Journal of Urban Economics 81(3): 136- 148.

[6] Ohls, J.C., R.C. Weisberg, and M.J. White (1974) The effect of zoning on land value. Journal of Urban Economics, 428-444.

[7] Rose, L.A. (1986) Urban Land Supply: natural and Contrived Restrictions. Journal of Urban Economics, 25: 325-345.

[8] Rothwell, Jonathan T. (2011). Racial Enclaves and Density Zoning: The Institutionalized Segregation of Racial Minorities in the United States. American Law and Economic Review 13(1): 290-358.

[9] Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, Emmanuel Saez (2014) “Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 19843.

[10] Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, and L Katz (2015) “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 21156.

[11] Furman, Jason (2015) Barriers to Shared Growth: The Case of Land Use Regulation and Economic Rents. Presentation at The Urban Institute, November 20.

[12] Hirsch, Jerry (2014) 3,000 Toyota jobs to move to Texas from Torrance. Los Angeles Times, April 28.

[13] Ganong, Peter and Daniel Shoag (2017) “Why Has Regional Income Convergence in the U.S. Declined?” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 23609.

[14] Dougherty, Connor (2016) Bay Area Start-Ups Find Low-Cost Outposts in Arizona. The New York Times, August 21.

[15] DeLong, Bradford (2016) NIMBYism in America: A Back-of-the-Envelope Finger-Exercise Calculation. Available at: http://www.bradford-delong.com/2016/08/nimbyism-in-america-aback-of-the-envelope-finger-exercise-calculation.html (last accessed 11/15/2016).

[16] Rosenthal, Stuart S. (2014) Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing? Estimates from a ‘Repeat Income’ Model. American Economic Review 104(2): 687– 706.

[17] Hankinson, Michael (2017) “When Do Renters Behave Like Homeowners? High Rent, Price Anxiety, and NIMBYism.” Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University Working Paper. Available at: http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/harvard_jchs_hankinson_2017_renters_behave_like_homeowners_0.pdf

[18] The following neighborhood councils did not post minutes on their website, did not face opposition to new housing developments, or did not review new housing developments in 2015: Arroyo Seco, Central Hollywood, Historic Cultural, Koreatown, MacArthur Park, Palms, South Central, West Adams

[19] Rothwell, Jonathan T. (2015) Zoning out the Poor: Skywalker Ranch Edition. Brookings Institution Social Mobility Memos, Wednesday, July 1.

[20] Pendall, Rolf (1999) Opposition to Housing: NIMBY and Beyond. Urban Affairs Review, 35(1): 112-136.

[21] Manville, M. and Osman, T. (2017), Motivations for Growth Revolts: Discretion and Pretext as Sources of Development Conflict. City & Community.

[22]Pendall (1999) found that of 182 projects studied, 62% saw protest from local residents using these means. Public comments and letters were the most common, with over 50 of 182 projects inciting them. Petitions were circulated against 36 of the 182 projects.

[23]In Los Angeles, the Westwood HPOZ and the United Neighborhoods character residential district.

[24]An extreme example from Vermont/Western requires project containing 40,000 square feet or more of retail commercial floor to provide free delivery of purchases made at the site to local residents.

[25]For example, the RHNA uses 2010 jobs numbers in projections, thus underestimates housing needs near rapidly growing job centers.

[26]For example, encouraging downzoning and discouraging upzoning, and setting conditions on properties or uses.

[27]For example, the Hollywood community plan, mobility element.

[28]For example: http://la.curbed.com/2013/1/3/10295162/leaked-settlement-shows-how-nimbysgreenmail-developers-1

[29]For example, the lawsuit against Accessory Dwelling Unit in the city of Los Angeles.

[30]Though not a new phenomenon (Orman, 1984), examples of ballot-box planning continue with San Francsico’s Proposition I, the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative in Los Angeles, and Encinitas’ Proposition A, which requires zoning amendments be approved by voters http://www.laweekly.com/news/should-we-build-more-housing-in-la-7056107

[31]Most recently, activists in Boyle Heights have been pressuring art galleries to leave the neighborhood using mild tactics of intimidation compared to the aggressive violence used by white neighborhoods against minorities throughout much of the history of US cities and to this day (Loewen, 2006).

[32] Lewis, Paul G. (2003) Housing Element Law: The Issue of Local Noncompliance. Public Policy Institute of California Report.

[33] Lens, Michael C. and Paavo Monkkonen (2016) Do Strict Land Use Regulations Make Metropolitan Areas More Segregated by Income? Journal of the American Planning Association 82(1): 6-21.